warning: some of the paintings might be disturbing to some, they show depictions of death, war, and gore.

This essay will discuss the international dimensions of the Cold War, with the specificity of the Vietnam War. The War lasted twenty years, from 1955 to 1975, and involved North Vietnam (with support from the Soviet Union and China) and South Vietnam (supported by the United States and its allies).

The different ways that the Vietnam War shows the international dimensions of the Cold War are through the proxy war, the ideology, and the global anti-war movements. These points will be further explored in the body of the essay. The artworks selected to represent these dimensions best are mainly by the American painter Leon Golub and some paintings, for comparative reasons, by Vietnamese artist Trưóng Hiếu. The comparison of these two artists, and specifically their paintings of the Vietnam War, allows for the demonstration of how the War was perceived from both sides.

Over two million Vietnamese civilians died during the War, according to the 1995 Vietnamese official estimate. This does not include the soldiers, nor American casualties. The War was a result of the ideological difference between the communists and capitalists, enforced by a ‘proxy war’ between the Soviet Union and the United States of America. The Oxford Dictionary defines a ‘proxy war’ as “conflicts in which a third party intervenes indirectly in a pre-existing war to influence the strategic outcome in favour of its preferred faction”. In this way, the Vietnam War was a perfect means for the two powers to keep the Cold War cold whilst still being able to go ‘head-to-head’.

However, eventually, the United States deployed troops into Vietnam and the proxy war was no longer. The Soviet Union, however, did not deploy troops into Vietnam, but rather supplied food, transportation, arms, and other commodities to help strengthen North Vietnam’s defences.The participation of the United States of America and the Soviet Union sparked protests across the globe – with anti-war movements becoming the norm. The main protests occurred in America, with the SDS March of Washington being the largest peace protest against the war; 15,000 to 25,000 students flocked to the capital to support the anti-war movement. The United Kingdom, and especially London, also had protests against the Vietnam War, urging the government to stop providing military arms to the United States – further showing the international impact of the Vietnam War.

The horrors experienced during the Vietnam War were unthinkable: over the course of ten years (1965 to 1975), the United States dropped more than seven and a half million tons of bombs on Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. To contextualise this, that is double the amount that was dropped on Asia and Europe during World War II, and is to this day, the largest aerial bombardment in history. Although we will never fully grasp what the people involved experienced, artists have sought to capture these terrors through paintings and drawings, especially American artists Nancy Spero and Leon Golub.

Golub and Spero were a married couple who lived together in New York. They both focused on political art, and the ‘dark side of human relationships’, therefore the Vietnam War was a perfect topic for them to depict – they both had a room dedicated to their art in the Tate Modern, London, for a year. Although both Spero and Golub painted the Vietnam War, this essay will only focus on Golub’s artworks. Golub was born in 1922, and so experienced the entirety of the Cold War and several devastating wars, such as World War II and the Korean War. This experience likely helped him capture the horrors of the Vietnam War with relative ease and allowed him to feel more comfortable with pushing the boundaries of political art.

Golub’s most impactful painting, regarding the Vietnam War, was Vietnam II. Vietnam II [Figure 1] is owned by the Tate Modern, after an acquisition in 2012 from Ulrich and Harriet Meyer, but is not currently on display. It is part of a trilogy of paintings all depicting the Vietnam War, however, Vietnam II is the most notable. The painting itself is on unstretched linen, which is over three metres high, and twelve metres long – it is Leon Golub’s largest piece of work.

The painting is a haunting and poignant reminder of the horrors of the Vietnam War. There is a large gap in the middle of the linen, which symbolises the clear divide between the two sides of the War – those fighting to ‘liberate’ and those forced to fight back. On the left, ironically, are the American troops, there to ‘liberate’ the Vietnamese people from the enemy, the communists [Figure 2].

The American troops are stationed in front of an armoured car, which is military green in colour; the men themselves are wielding machine guns, pointed directly at the Vietnamese people featured on the right side of the linen. The troops are all painted with their skin predominantly red, this could represent the bloodshed that they have caused, whether the red is the blood of those they have killed, or just emphasising their devilish nature and actions. The men appear to have expressions of aggression, aimed towards the civilians on the right. On the right side of the linen, there are Vietnamese civilians which can be seen in Figure 3.

Although there are more civilians than the American troops (eight to three) it is made obvious that they are at a disadvantage. Instead of an armoured car behind them like the American troops, they have ash-covered house foundations which we can deduce as having been destroyed by the troops. The most harrowing aspect of this painting is the Vietnamese boy featured in the front – he is seemingly young, with an expression of anguish as he stares directly at the viewer, drawing us in, and urging us to help him. The younger members of the Vietnamese civilians are running, evidently in distress, whereas the older members seem to be much calmer, almost as if they have accepted their fate – the Vietnamese woman furthest away from us is looking at the American troops, brandishing a murderous gaze.

They are all covered in ash, just like their house, emphasising their position as victims. Golub has stated that he sources from contemporary news photographs – this allows for the positions and facial expressions to be factual. Furthermore, the cuts in the linen are purposeful and precise, they are meant to “echo the violence depicted in the image in an assault on the fabric of the artwork”.

Golub had originally titled this Vietnam series to be called ‘Assassins’, further highlighting Golub’s position and belief about the War. This painting shows the international dimensions of the Vietnam War, and in-turn the Cold War because it shows the impact that it had on America, and how people were so desperate to portray it in art. As well as this, the fact that it is owned by the Tate Modern shows that the impact of the Vietnam War spread globally.

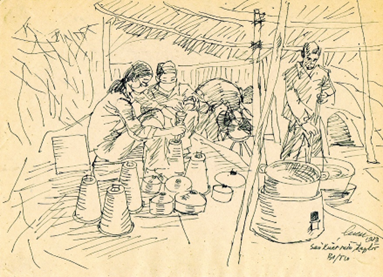

This painting is an example of a painter depicting the War from photographs, a secondary source, whereas most of the paintings and drawings of the Vietnam War by Vietnamese artists are primary sources, created during the conflict. An example of this is the drawings by soldier Trưóng Hiếu, who documented the first-hand experience of the War through art. The paintings Hiếu created are the everyday lives of the Vietnamese soldiers, as seen in his drawing “Hieu 1973; Sản xuất mìn” which translates to “Production of mines” [Figure 4].

Here, the Vietnamese soldiers who are creating landmines have been sketched by Hiếu – the fast-sketching style allows for the viewer to be placed in the scene, as the fast motion of the lines creates movement. It also alludes to the rushed nature of the drawing – as if they need to produce the mines quickly. However, out of the drawings that Trưóng Hiếu created of the Vietnam War, one piece stands out, this is the drawing “Du kích, Hieu 1973”, which translates to “A guerrilla” [Figure 5].

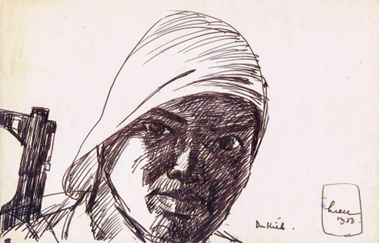

This drawing features a Vietnamese soldier with a pointed stare – the dark lines upon the face emphasise the stare, and even make it feel sinister. The fact that the Vietnamese soldier is slightly looking down makes the viewer feel as if they are there with the soldier like they are going to join the guerrilla attack themselves. The rushed lines highlight the limited time that Hiếu would have experienced, this drawing was created before a guerrilla attack. The soldier with the gun shows a different side to the War; unlike Golub’s Vietnam II, as seen in Figure 1, the Vietnamese man does not feel helpless, it could even de-victimise him.

In most American depictions of the Vietnam War, the people are portrayed as helpless victims, whereas, in Vietnamese art, they are shown to fight back – not just allow the American troops to ‘liberate’ them. It is interesting to see the difference between the art of American artists, who had no direct involvement in the War, and the Vietnamese artists who were drawing from what they could see in front of them.

Although Vietnam II is likely the most prominent painting by Golub regarding the Vietnam War, he also produced a series called ‘Napalm’. Napalm is “a weaponised mixture of chemicals designed to create a highly flammable and gelatinous liquid” and it can cause horrific burns. It was infamously used by the American troops in the Vietnam War. The first of Golub’s Napalm series ‘Napalm I’ [Figure 6], painted in 1969 is the most notable of the collection.

It is three metres tall and five metres in length. The painting is painful to look at, with the men in clear pain and panic. One of the men is on the floor, red marks covering his chest whilst his facial expressions cannot be described as anything other than agony. The technique used by Golub of scraping paint away to reveal different colours is extremely impactful, especially in this work: the removal of the paint layers is eerily similar to how napalm removes layers of human skin, with the burns being extremely damaging. The men are both naked, showing that they are in their most vulnerable form, it could also be symbolising that they are civilians rather than Vietnamese soldiers.

Another example of this is in Head-Napalmed (1971) [Figure 7] which was also part of the Napalm series. This painting is different however because it features just the head of a man, which begs the question, where is the rest of his body? Whether it is a decapitated head, or Golub just chose to paint only the head is unknown. Regardless of this, the head is almost entirely red, with the same scraping technique being used. The scraping is done carefully and purposefully, rather than erratic. The face somehow seems still, this is likely because the mouth is only in a line, whereas Golub normally demonstrates suffering through large facial expressions – therefore, is this man now at peace?

Furthermore, the man’s gaze is directed away from the viewer; Golub normally paints eyes towards the viewer, which could further show the man’s position as deceased. Both of these paintings were produced on unstretched linen, much like Golub’s previously mentioned painting Vietnam II – this gives the illusion that it has been painted on foraged fabric as if he had to paint on whatever materials he could find; this makes the painting feel raw and make-shift. It could also give the feeling that it has been painted on a banner, which was massively used during protests, but also was used as a way to spread propaganda. It is unlikely, however, that Golub would purposefully make propaganda art regarding the Vietnam War and is more likely to be an anti-war protest banner.

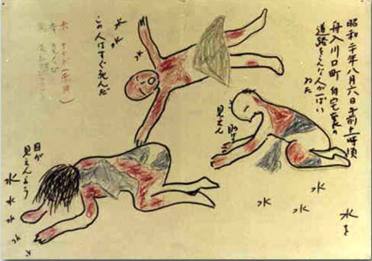

Golub’s art, especially his Napalm Series, could be compared to the drawings made by Japanese people in response to the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. As a way to help the victims ‘cope’ with what they had seen, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, also known as NHK, established a television show, and exhibition in 1975. John Hersey, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his book ‘Hiroshima’, stated in response to this exhibition that the drawings were “more moving than any book of photographs of the horror could be, because what is registered is what has been burned into the minds of the survivors”

Golub’s works are most similar to ‘Victims Beg for Water and Cry Out That They Can Not See’ by Uesugi Ayako from 1945 [Figure 8]. The use of rushed red lines to convey burns and the removal of layers of skin is extremely similar to the method used by Golub. As well as this, the positions and facial expressions are haunting in the same way that Golub’s artworks are. Leon Golub has managed to convey the same amount of suffering and anguish in his paintings as the first-hand experiences of the victims of the atomic bomb in Japan. The experiences that the victims of napalm in Vietnam went through during the War are similar to what the victims in Japan went through – and bombing by American troops caused both.

Art in the Soviet Union regarding the Vietnam War had a very different message than the art being produced in the United States; it was all propaganda. The propaganda created depicts how the Soviet Union is helping North Vietnam, usually through two men shaking hands, and just being overall friendly towards each other, as can be seen in Figure 9. This propaganda shows, as previously mentioned, two men, from each country, holding hands in a grateful manner. They are both framed by their respective country’s logos in the iconic communist colours – red and gold.

Both men are in working-man clothes, showing their relatability to the common people. The text in the middle states “The distance is great, but our hearts are close!”. This depiction of the war is extremely different to the anti-war message spreading in America and across the globe. Although the Soviet Union was strict and regulated art and artists, this production of peaceful artwork might be due to the peaceful involvement that the Soviet Union had during the Vietnamese War. This was fairly different to the propaganda produced in Vietnam at the time – the themes most often portrayed a glorification of military action, for example, shooting down American planes.

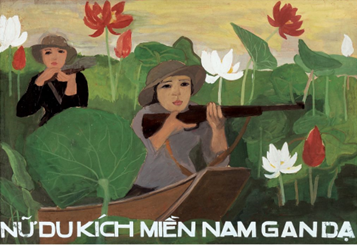

Moreover, women were often depicted as front-line fighters [Figure 10], which may have been trying to show that women were just as important in the War as men were – the text featured declares that “The southern guerrillas are truly gutsy”, further establishing this point. This particular piece of propaganda includes lotus flowers, the national symbol of Vietnam, alluding to the idea of being proud to fight for your country.

Therefore, the Vietnam War shows the international dimensions of the Cold War. This is through its position as a proxy war which started with the ideological difference, as well as sparking huge anti-war protests, mainly in the United States of America and the United Kingdom. These protests have been emphasised through art – with American artists such as Leon Golub producing haunting paintings of the victims of the Vietnam War. These paintings help the viewer understand just how devastating the War was, and how so many people were affected by the actions of American troops. The juxtaposition between the art of the Western artists and the art of the Vietnamese artists is staggering – the Vietnamese art (including the propaganda) was created on the spot, in the middle of the War; the lines tend to be rushed and quick, emphasising movement.

The subjects of the artworks tend to be Vietnamese soldiers, portrayed as heroes, rather than victims like the American paintings show them to be. This might be due to the more open anti-war sentiments in the West, whereas in Vietnam and the Soviet Union, propaganda still reigned supreme. These depictions have been seen all over the world, with many of Golub’s Vietnam paintings being owned (and displayed) by the Tate Modern, allowing viewers to see how the War was viewed by both sides, especially since many people never experienced it.

““The Artist as an Angry Artist: The Obsession with Napalm” | Repensar Guernica.” Guernica.museoreinasofia.es, guernica.museoreinasofia.es/en/document/artist-angry-artist-obsession-napalm. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

“A Peaceful March – except in Grosvenor Square.” The Guardian, 28 Oct. 1968, www.theguardian.com/theguardian/1968/oct/28/fromthearchive.

BBC. “The Vietnam War – CCEA – Revision 8 – GCSE History – BBC Bitesize.” BBC Bitesize, 2019, www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z8kw3k7/revision/8.

Dower, John W. “Ground Zero 1945 | Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors.” Visualizing Cultures, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2008, visualizingcultures.mit.edu/groundzero1945/gz_essay.pdf. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

Editors of Britannica. “How Many People Died in the Vietnam War? | Britannica.” Www.britannica.com, 14 Apr. 2023, www.britannica.com/question/How-many-people-died-in-the-Vietnam-War.

Espionart. “Unforgettable Pictures of Hiroshima.” ESPIONART, 8 Aug. 2014, espionart.com/2014/08/08/unforgettable-pictures-of-hiroshima/. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

Guldner, Gregory T., and Curtis Knight. “Napalm Toxicity.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537127/.

Irvine, Dean. “Vivid Propaganda Posters of ’50-’70s Vietnam.” CNN Travel, 18 Mar. 2015, edition.cnn.com/travel/article/cnngo-travel-vietnam-propaganda-poster-art/index.html.

“Jason Mones on Leon Golub.” Painters on Paintings, 4 June 2015, paintersonpaintings.com/jason-mones-on-leon-golub/. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

McLean, Iain, and Alistair McMillan. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. 3rd ed., OUP Oxford, 26 Feb. 2009.

Tate. “Leon Golub 1922–2004.” Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/leon-golub-2207.

—. “Leon Golub and Nancy Spero – Display at Tate Modern.” Tate, www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/display/artist-and-society/leon-golub-and-nancy-spero.

Taylor, Rachel. ““Vietnam II”, Leon Golub, 1973.” Tate, 2004, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/golub-vietnam-ii-t13702.

“The March on Washington · Exhibit · Resistance and Revolution: The Anti-Vietnam War Movement at the University of Michigan, 1965-1972.” Umich.edu, 2021, michiganintheworld.history.lsa.umich.edu/antivietnamwar/exhibits/show/exhibit/the_teach_ins/national_teach_in_1965.

Thomas, Cooper. “Bombing Missions of the Vietnam War.” ArcGIS StoryMaps, 8 June 2021, storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/2eae918ca40a4bd7a55390bba4735cdb.

2 responses to “Leon Golub: how does his work show the international dimensions of the Cold War?”

Thanks Holly.

Great paper.

The most revealing documentary I have seen is:

“THE VIETNAM WAR, an 18 hour documentary film series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick for America’s Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).

In an immersive narrative, Burns and Novick tell the epic story of the Vietnam War as it has never before been told on film. THE VIETNAM WAR features testimony from nearly 80 witnesses, including many Americans who fought in the war and others who opposed it, as well as Vietnamese combatants and civilians from both the winning and losing sides. Six years in the making, the series brings the war and the chaotic epoch it encompassed viscerally to life. Written by Geoffrey C Ward, produced by Sarah Botstein, Novick and Burns, it includes rarely seen, digitally re-mastered archival footage from sources around the globe, photographs taken by some of the most celebrated photojournalists of the 20th century, historic television broadcasts, evocative home movies, and revelatory audio recordings from inside the Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon administrations.

quoted from Amazon.”

Includes extensive testimony from Vietnamese. And from Americans who, having survived combat, returned home to witness anti-war protests & their own National Guard shooting (& even killing) student protesters. One of those guys talking on film, Tim O’Brien, wrote a very interesting book, The Things They Carried, five short stories which read like five chapters of the same novel.

The first chapter is written around all the things they did carry, a recurring motif:

“Often, they carried each other, the wounded or weak. They carried infections. They carried chess sets, basketballs, Vietnamese-English dictionaries, insignia of rank, Bronze Stars and Purple Hearts, plastic cards imprinted with the Code of Conduct. They carried diseases, among them malaria and dysentery. They carried lice and ringworm and leeches and paddy algae and various rots and molds. They carried the land itself – Vietnam, the place, the soil – a powdery orange-red dust that covered their boots and fatigues and faces.”

“A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil.”

Nick

Oh wow that does sound amazing! I’ll have to do some research on that.