This essay will focus on Urbanisation in the British empires, specifically the City of London, with a particular emphasis on how it affected the spread of diseases.

Urbanisation is the “increase in the proportion of people living in towns and cities”. This occurs due to the amount of people moving from more rural areas, such as the countryside, to more urban areas, like cities, and in this case, London.

The majority of the British population now live in cities, almost 85 per cent, compared to 27.5 per cent of the population in 1801. There were many reasons for this influx of people due to urbanisation, including industrialisation, employment prospects, and social opportunities.

However, this leads to negative impacts for certain groups of people. In the 19th Century especially, the working class, women, and children were most negatively affected. The increased number of people, and livestock, and the lack of space for them all amplified the poor sanitation, causing an upsurge in disease in the poorer areas.

During the mid-19th Century, the death rate among children had decreased the average life expectancy in the City of London to thirty-seven years, due to diseases spread amongst the poor such as cholera and typhoid. As well as this, the employment prospects were mainly factory jobs, where the working conditions were unsuitable and dangerous.

The sudden inflow of working-class people into London led to a widening of the class gap, which in turn properly established the Middle Class, leading to a new minority group being affected. The increased mortality due to Urbanisation became known as the ‘Urban Penalty’ – this is specifically when “cities concentrate poor people and expose them to unhealthy physical and social environments”.

In 1801, on March 10th, the first census in Great Britain was undertaken. It was divided by parish or town and focused mainly on how many families lived in one house, what a person’s employment was, their gender, how many baptisms and burials there were, and how many marriages occurred.

There were three types of census records, that of the individual, then of the household, and one that was sent to London and used for statistics. This documentation of how many families lived under one roof is useful to follow urbanisation and show how the living conditions would have affected mortality.

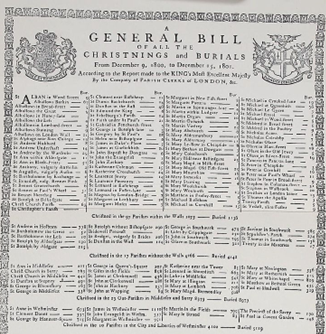

Before the census, the way that people were recorded, and my main focus, were the Bills of Mortality. These were made by the monks of the parish and can be found as far back as 1593.

These documents are useful for a different reason than the census, unlike the census they do not give us an idea of the individuals but rather an idea of the conditions that they lived in and what was the most prevalent cause of death.

The Bill of Mortality that I will be evaluating can be seen above and is from the Parish Clerks of London from the 9th of December 1800 to the 15th of December 1801, this is Figure 1.

Bills of Mortality became much less common in the 19th Century, with the census acting as its replacement. The document from 1801 highlights what were the most prevalent causes of death in the year.

For example, using the chart we can see that what was the number one killer of the time was Consumption – which is what we now know as tuberculosis. This gives us an insight into what kind of living conditions were common at the time in London.

Tuberculosis, an infectious disease caused by bacteria that affects the lungs, as well as many other diseases at the time was easy to contract if you had a weak immune system, which was the case for many of the working-class people of the time – they lived in cramped, unsanitary conditions with poor nutrition.

As well as this, London was known as the ‘Big Smoke’ – all of the factories and businesses caused the air to become extremely polluted, which caused further health issues.

Furthermore, manufacturers could not keep up with the influx of new individuals in London, leading to poor sanitation within the food industry, which increased the likelihood of being infected with Tuberculosis.

This is the case regarding milk especially. In 1882, 20,000 milk samples were tested, and it showed that a fifth of the milk had been contaminated.

Although many working-class people did not drink milk themselves, they gave it to their children. Milk vendors, more often than not, kept the milk uncovered, left for the flies and any other bacteria to breed – the majority of the time milk was already four days old when it reached the buyers.

It was found that in 1903, 32 per cent of the milk tested in Finsbury contained pus, a fluid that comes from the site of an infection, and 40 per cent contained dirt.

The milk’s state as unpasteurised and kept in unsanitary conditions made it a perfect breeding ground for Bovine TB to multiply – this had a very high potential of causing Tuberculosis in humans, especially in infants who had a weak immune system.

Once the baby has contracted Tuberculosis from the milk, they would cough and spread it to the rest of their family, since it is transferred through the air. From there, the family spreads it to the other families in the household and they spread it to the people they work with, and since they are all working-class, they would have had weaker immune systems than the wealthier and therefore they are susceptible to consumption.

This is evident in the Bill of Mortality from 1801 (seen above), with 4,695 people in London dying from consumption in the year. 5,395 of the individuals who died in that year were under two years of age, however, we know that 407 of those were Abortive or Stillborn. Therefore, 4,988 infants died of disease, most likely due to factors that could have been easily prevented.

This increased the mortality of infants of all classes, not just the working class. Many of the diseases that caused the majority of deaths could have been easily prevented; a better diet, better housing, and more concern for the working class would have prevented many deaths. It demonstrates how vulnerable the minority groups of the time were, especially the infants.

The Industrial Revolution, and in turn the increase of urbanisation in London, allowed for a further divide in the classes, creating a middle class – known as the ‘middling sort’.

However, it is debatable when the Middle Class was fully established due to the differing definitions over the years. The position of someone in the Middle Class was more dependent on their occupation rather than income, which is how we define it now.

An example of this is that an engineer could earn more than a clerk, but due to his position as an engineer, he is of the lower class, whereas a clerk might earn less than an engineer, but due to his employment as a clerk, he is considered Middle Class. Of course, a woman’s position depended entirely on her father or husband. Luxuries became more of a ‘necessity’ in this period, with the new capitalist market targeting this new Middle-Class Woman more than any other group. Middle-class women took pride in their homes, as there were more people in the city due to urbanisation, which led to houses becoming more of a luxury.

The Industrial Revolution brought about many new inventions to make their household more aesthetic. However, the revolution also brought about many new scientific discoveries which were thrust upon the Victorian woman. In 1851, the infamous window tax was repealed after one hundred and fifty years. The increase of people living in London due to urbanisation meant that the window tax was causing more issues than not – the lack of necessary light and ventilation led to an upsurge in typhus, smallpox and cholera.

Ironically, the tax produced a positive impact on the health of the poor, but this was at the expense of the Middle Classes’ health; the decoration of the Victorian home did not need to be as practical – they could decorate the walls with vivid, deep-coloured wallpaper. A popular colour during this period was ‘Scheele’s Green’, most commonly found in Morris & Co’s floral wallpaper. The colour was named after the scientist Charles William Scheele, who established the method of making the pigment.

This colour, however, contains the deadly compound arsenic. This would not have been an uncommon ingredient at the time; arsenic was found in many different domestic products in the Victorian home, such as make-up. Arsenic allowed for a bright, vivid colour to be produced, making it the perfect ingredient for wallpaper. The shade of green that was ‘Scheele’s Green’ was so popular at the time that it was estimated that within the walls of the Victorian homes, in London, one hundred million square miles of arsenic-filled wallpaper could be found.

Bartolomeo Gosio, an Italian chemist, discovered in 1891 that people were falling ill and dying from the gas released by a deadly combination of pigment, fungi, and wallpaper paste. Children were especially at risk, due to a much weaker immune system from lack of nutrition and unhealthy living conditions – it was reported that in 1862, four children who shared a room lined with Scheele’s Green wallpaper in the East End died.

These ‘mysterious ailments’ continued for years because the Middle Class began to travel to the seaside at the weekends, due to public transport being far more accessible; this meant that the families would receive a break from the toxic gas swimming around their houses, and their symptoms would disappear.

As well as this, the symptoms of arsenic poisoning, difficulty breathing, headaches, heart failure, and paralysis were extremely similar to those of the common disease diphtheria, a serious infection. This caused a lot of scepticism from politicians over whether the wallpaper was dangerous.

In 1869, a medical doctor from New York, W. W. Hall, had criticised the arsenic wallpaper, and established it as a ‘health hazard’ – it was not long after that the doctors in England started stating the same information. However, the doctors who expressed their concerns about the arsenic-laden wallpaper were publicly ridiculed, including by the prolific artist and user of Scheele’s Green, William Morris.

Morris was at the forefront of the wallpaper design trade, and so his words regarding the compounds of his wallpaper were ‘taken as gospel’. Morris did not believe that arsenic had such toxic effects, going as far as to outwardly declare that he believed it was a hoax that the doctors were spreading. This blatant lack of concern for the health of his customers shows that the Industrial Revolution, and in turn urbanisation, had produced a new mindset of exploitation and work ethic.

This new form of work ethic, by which the exploitation of minorities increased, allowed for shortcuts to be taken. It was only in 1844 that Parliament passed a Factories Act that declared that all dangerous machines should be confined and that no children should clean machinery when it was in motion.

This Act was just one of many that aimed to prevent mortality and injuries in the workplace, but the fact that these acts needed to be established reveals how poor the conditions must have been.

The most infamous and memorable case of dangerous working conditions of the time is the story of the Match Girls. The girls took industrial action and staged a walk-out protest against these conditions in 1888. In the factory, there was no separate area for the employees to eat their lunch – not only would they not have a break from the fumes from the phosphorus that was used to make matches, but they would also be consuming contaminated food.

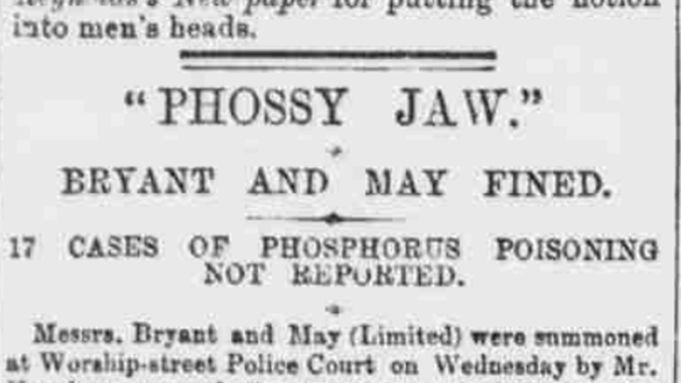

Furthermore, these work conditions caused what is known as the ‘phossy jaw’ – also known as phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, which is a disease in which the jaw bone starts to slowly become exposed. Extremely painful abscesses would develop in the mouth, which caused facial defects and often severe brain damage or death.

The co-owners of the factory, Bryant and May, had switched from using the safe, non-toxic red phosphorus to the poisonous white phosphorus. This change was because the white phosphorus was a lot cheaper than the red, and also allowed for ‘strike-anywhere’ matches to be produced. These matches could be, as the name suggests, ignited anywhere – this was revolutionary in the matchstick community, and it made an extremely large profit.

The disease only affected the poor – those who would be exposed to these conditions, regardless if whether it had such dangerous work conditions. Furthermore, Bryant and May, the co-owners of the factory, did not provide any protection for the girls from the phosphorus, nor did they show any concern for the health of their workers.

It was reported in Reynold’s Newspaper, Sunday 5th of June, 1898, that Bryant and May were fined for not having declared seventeen cases of phosphorus poisoning; they had even claimed that their workforce was “healthy and unaffected”. Headline seen below.

This blatant lack of regard for their employees’ health and safety was dangerous and even led to mortality. The disease could have easily been prevented if the company had switched over to the more expensive phosphorus and followed health and safety protocols. Urbanisation played a key part in this – the influx of people in London at the time meant that the owners of companies, such as Bryant and May, could successfully exploit those who were minority groups, and an increased population meant more matches needed, which upsurged demand for a factory workforce.

Disease and disgusting odours became common in London in the 1850s, with the Great Stink occurring in the summer of 1858. Urbanisation meant that there were more people, meaning more sewage – the homes of the poor were not built with flushing toilets, and so most of the excrement ended up in the Thames. Even in those houses that did have a flushing toilet, the waste would still find its way into the Thames.

The lack of sanitary precautions, which increasingly became worse due to the rising population, led to outbreaks of disease, with two of the most fatal epidemics being the Cholera outbreak of 1833. 4,000 to 7,000, and in 1853, up to 12,000 people died. The doctor John Snow traced the 1833 epidemic to a water pump located on Broad Street – his findings show that if it were not for the poor, cramped, unsanitary living conditions, this disease would not have spread as viciously as it did.

Although Snow was ridiculed at the time by his fellow doctors, the discovery he made would eventually lead to sanitation and cleanliness becoming a priority of the people. Cleanliness started to be linked to the ideas of respectability and morality – it became ingrained into society that ‘cleanliness was next to Godliness’. This extract can be linked to the Old Testament; it means that people have a ‘moral’ duty to keep their bodies and homes clean.

Furthermore, the ‘Great Stink’ allowed people to realise the connection further, with the parliament of the time being so disgusted by the smell they were forced to build a sewage system for the City. Urbanisation, although it caused a lot of disease and deaths in the early 19th century, actually had a silver lining; all of these epidemics and mortalities allowed scientists and doctors to make discoveries that would help prevent these issues again.

The sewage system is an example of this, as well as the discovery of germs, and the need to wash your hands. The influx of people in the city called for more laws, health and safety, and overall care. Although at the time thousands of people’s deaths could have been prevented if there had been more precautions and laws put in place, eventually their deaths led to these being put in place, preventing any further unnecessary deaths.

The creation of the sewage system, however, could be viewed as having only been put in place for the middle and upper classes rather than for the poor, although this mastery of engineering did benefit the poor greatly.

This essay has demonstrated how urbanisation has affected mortality through sanitation issues, dangerous work conditions, lack of scientific knowledge, and how they eventually led to the discovery of how these were causing health problems. Urbanisation negatively affected mortality, as mentioned, the lack of accommodation for the sudden influx of people led to cramped conditions, poor sanitation, and exploitation.

This allowed for disease to be rife and kill thousands of minority groups, affecting especially infants; epidemics were always common in England; however, they did increase since the beginning of the 19th century due to urbanisation.

However, mortality did not just come from poor living conditions, but also from ‘luxuries’; as mentioned, green wallpaper, specially made by Morris & Co., was a luxury that was enjoyed mainly by the middle and upper classes. This wallpaper contained arsenic, which was poisonous and caused many Victorian households, especially children, to become sick and even die.

Urbanisation caused owning a house to become a luxury in itself, and so those who had a house to themselves took pride in it, wanting to decorate it with such bold colours as this green wallpaper, leading to their deaths. Moreover, the many new, desperate people living in London also permitted a new type of exploitation.

Many minorities, at the time, were lucky to be employed, let alone get paid, and the employers knew this and made sure their employees knew that they were dispensable – the work conditions were dangerous, with injuries, and even death, in the workplace being commonplace.

Although these work conditions were unsafe, they caused the workers to speak up and get workplace health and safety laws established, which in turn prevented more employees from being exploited. So many minorities in the 19th century died at the hands of preventable diseases, due to the industrial revolution and urbanisation.

Many of these diseases are understood and are very rare in our modern society due to the thousands of lives that succumbed to them at the time. Urbanisation affected mortality negatively at the time, however, it benefitted those who came after them, as many laws and precautions were established to protect citizens in urban cities for future generations.

Bibliography

Alvarez-Palau, Eduard, Dan Bogart, Oliver Dunn, Max Satchell, Shaw Leigh, and Taylor. 2020. “Transport and Urban Growth in the First Industrial Revolution.” https://www.campop.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/occupations/outputs/preliminary/marketaccesspresteam.pdf.

Brend, William A. 1907. “Bills of Mortality.” Transactions of the Medico-Legal Society for the YearÖ MLST-5 (1): 140–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1051449×0700500108.

European Environment Agency. 2023. “Urbanisation — European Environment Agency.” Www.eea.europa.eu. 2023. https://www.eea.europa.eu/help/glossary/eea-glossary/urbanisation.

Freudenberg, Nicholas, Sandro Galea, and David Vlahov. 2005. “Beyond Urban Penalty and Urban Sprawl: Back to Living Conditions as the Focus of Urban Health.” Journal of Community Health 30 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-004-6091-4.

Haslam, J. C. 2013. Deathly Decor: A Short History of Arsenic Poisoning in the Ninteenth Century. Vol. 21. Res Medica .

“IBISWorld – Industry Market Research, Reports, and Statistics.” 2023. Www.ibisworld.com. July 11, 2023. https://www.ibisworld.com/uk/bed/urban-population/44231/.

Isaac, Susan. 2018. “‘Phossy Jaw’ and the Matchgirls: A Nineteenth-Century Industrial Disease.” Royal College of Surgeons. Royal College of Surgeons. September 28, 2018. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/phossy-jaw-and-the-matchgirls/.

Jennings, Jan. 1996. “Controlling Passion: The Turn-of-The-Century Wallpaper Dilemma.” Winterthur Portfolio 31 (4): 243–64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1215237?seq=13.

Kelleher , K. 2018. “Scheele’s Green, the Colour of Fake Foliage and Death.” The Paris Review. 2018. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/05/02/scheeles-green-the-color-of-fake-foliage-and-death/.

Koven, Seth. 2014. The Match Girl and the Heiress. JSTOR. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qh0wr.6?searchText=the+match+girls&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dthe%2Bmatch%2Bgirls%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3A61ac59fc94556db5c0e044d278de1b47&seq=9.

Lipscomb, Suzannah . 2013a. “Hidden Killers of the Victorian Home – Full Documentary.” Www.youtube.com. 2013. https://youtu.be/Sy7iUoWi_-U?feature=shared.

———. 2013b. “10 Dangerous Things in Victorian/Edwardian Homes.” BBC News, December 16, 2013, sec. Magazine. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-25259505.

Morris, William. 2014. The Collected Letters of William Morris, Volume I. Princeton University Press.

Museum of London. 2017. “Air Pollution, the Great Stink & the Great Smog | Museum of London.” Museum of London. Museum of London. August 24, 2017. https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/londons-past-air.

“Register | British Newspaper Archive.” 1898. Www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. June 5, 1898. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000101/18980605/003/0001.

Sharples, S. P. 1876. “Scheele’s Green, Its Composition as Usually Prepared, and Some Experiments upon Arsenite of Copper.” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 12 (12): 11–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/25138431.

“The 1801 Census.” n.d. Www.1911census.org.uk. https://www.1911census.org.uk/1801.

“The Rise of the Middle Classes | the Victorian Era.” n.d. Author vl McBeath. https://www.valmcbeath.com/victorian-era-england-1837-1901/the-rise-of-the-middle-classes/.

Tynkkynen, K. 1995. “[Four Cholera Epidemics in Nineteenth-Century London].” Hippokrates (Helsinki, Finland) 12: 62–88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11609122/.

UK Parliament. 2019a. “Later Factory Legislation.” UK Parliament. 2019. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/19thcentury/overview/laterfactoryleg/.

———. 2019b. “Window Tax.” UK Parliament. 2019. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/about-the-group/housing/window-tax/.

Wall, Richard, Matthew Woollard, and Beatrice Moring. 2004. “Department of History Research Tools Census Schedules and Listings, 1801- 1831: An Introduction and Guide No 2.” https://www1.essex.ac.uk/history/documents/research/RT2_Wall_2012.pdf.

WHO. 2023. “Tuberculosis (TB).” Www.who.int. April 21, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis#:~:text=Tuberculosis%20(TB)%20is%20an%20infectious.

Whorton, James C. 2011. The Arsenic Century : How Victorian Britain Was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wohl, Anthony S. 1983. Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain. Cambridge: Harvard UP.